Theoretical physics: the scientific revolution that peaked in the early 1900s.

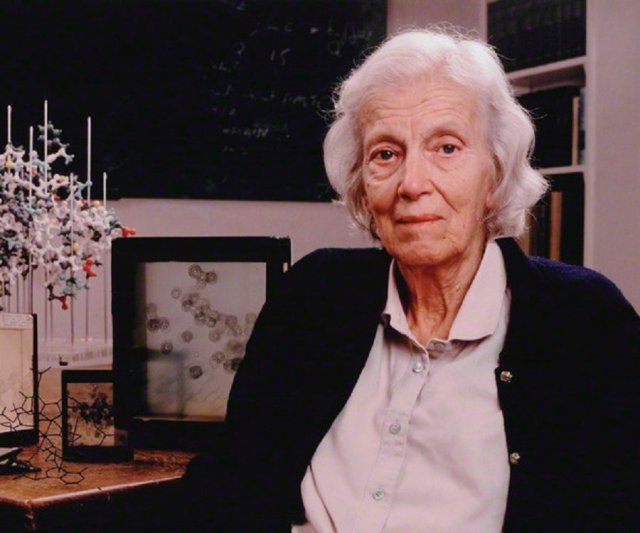

This particular field of study is littered with names of famous men: Albert Einstein, Max Planck, James Clerk Maxwell, Ludwig Boltzmann, and more. These men, among many others, made incredible contributions to theoretical physics and changed the way we understand physical science. But there are a few women who boldly ventured into this testosterone-ridden field. Lise Meitner was one of them.

Meitner was born in 1878 to a wealthy Jewish family in Vienna. At the time, women were barred from attending institutions of higher education. But she desperately wanted to learn, so her family privately funded her education.

In 1905, she became the second woman ever to earn a doctorate in physics from the University of Vienna. From there she traveled to Berlin, where fate would bring her into the crosshairs of legendary people like Planck and Einstein.

At first, Planck refused to teach women. Meitner attended his lectures on theoretical physics regardless and soon became his research assistant. It was in Planck’s lab that she met Otto Hahn.

Hahn was a chemist – a great chemist, and they were a great team. Together they discovered new isotopes, studied beta radiation, and took on some of the biggest scientific challenges of their time.

In 1912, the duo moved to the new Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin. Despite being a team, Meitner worked without pay under Hahn’s leadership. She eventually garnered a paid position, and in 1917 was named head of her own physics department. Theoretical physics was a competitive field at the time, with the very basics of atomic and molecular theory being called into question. The competition became obvious in 1923.

Meitner made a discovery in 1922 – she noticed that if an electron was removed from the inner shell of an atom, an electron from a higher shell would move to fill the vacancy. This caused a release of energy unique to the element. She published these results in 1922. However, a French chemist Pierre Auger, independently published the same results in 1923. To this day, the phenomenon is called the “Auger Effect” despite Meitner’s discovery made a year earlier than Auger’s.

Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 certainly complicated matters. At first, her Austrian citizenship was enough to keep her safe. But eventually, it became clear that she would have to flee. She escaped to Sweden where she continued her work in private. By now, researchers had discovered the neutron and scientists were trying to decide if you could make elements heavier by bombarding them with neutrons.

Hahn and his colleagues were performing these neutron bombardment experiments, but he was baffled by the results: neutron bombardment created lighter elements. He couldn’t decipher a reasonable explanation for the results, so he secretly consulted Meitner.

“Perhaps you can come up with some sort of fantastic explanation. We knew ourselves that uranium can’t actually burst apart into barium.” – Hahn in a letter to Meitner

And here is where Meitner’s claim to fame comes into the picture – she came up with the theory of nuclear fission, which explained Hahn’s results. And when Hahn published his chemical evidence for nuclear fission, she was not listed as a co-author.

In February of 1939, Meitner published her own paper in the journal Nature called “Disintegration of Uranium by Neutrons: A New Type of Nuclear Reaction.” Regardless, she was overlooked by the Nobel Prize Committee in 1944 when they awarded Hahn with the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. It is rumored that Hahn felt incredibly guilty about this oversight, and independently submitted Meitner’s work to the Nobel Prize committee over ten times. But to no avail.

Meitner, alongside scientists like Einstein, recognized the incredible power of nuclear fission. She knew it could be harnessed into a dangerous weapon. She was offered a job to work on the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, to which she said “I will have nothing to do with a bomb.”

She didn’t go entirely unrecognized – she was awarded Woman of the Year in 1946 by the National Press Club in a visit to the United States to meet the President. She and her colleagues were also awarded the prestigious Enrico Fermi Prize in 1966. Unlike most women of the time, she held high-ranking academic positions and received a salary.

But science is a collaborative practice – very rarely is a discovery made by a single person. Credit must be given where credit is due. Otto Hahn did not discover nuclear fission alone. Meitner’s story defines the scientific revolution regarding theoretical physics: fierce competition, incredible discoveries, and accrediting the theories that explain our world.